Terrestrial biodiversity

Terrestrial biodiversity refers to the variety of lifeforms that exist in a particular place. It includes genetic, species and ecosystem diversity and all the interactions between them.

Here are the current issues our terrestrial ecosystems and biodiversity face in Canterbury/Waitaha.

Issue: The degradation of habitat outside public conservation land

Changing land use

The maintenance and protection of indigenous biodiversity remains a significant issue for our region.

The biodiversity of Waitaha contributes significantly to overall biodiversity in New Zealand/Aotearoa but there continues to be ongoing loss and degradation of indigenous habitat.

Outside legally protected conservation areas, this loss has largely been driven by how people have developed and used land.

Thousands of hectares of indigenous vegetation have been cleared over time, mostly for farming, transport infrastructure and urban development.

The ecosystem health of remaining undeveloped areas has also declined due to fragmentation and cross-boundary effects from developed or irrigated land, and pest and weed incursion.

The Land Cover Database (LCDB) series confirms that we have continued to lose high- and medium-quality land cover (habitats) across our landscape, changing these into low-value habitats where indigenous plants and animals cannot flourish.

Changes to the climate of Waitaha will impact the region’s indigenous biodiversity and ecosystems. In the short-to-medium term, it is the human response to climate change (for example, incentives to plant exotic conifer forests such as radiata pine, build more and larger flood protection works on the coast and floodplains, and more intensive land uses) that will likely become a new driver for further loss of indigenous biodiversity and ecosystems.

This map shows the change in the distribution of low, medium and high-quality habitat types between 1996 (on the left) to 2018 (on the right) and includes district and city council boundaries. Use the plus and minus buttons to zoom to a particular location and the slider to see the change between the years.

Green represents high-quality habitat where indigenous plants and animals can thrive.

Orange represents medium-quality habitat where indigenous plants and animals can live.

Red represents low-quality habitat where indigenous plants and animals find it difficult to live.

Quality of Waitaha habitat for indigenous plants and animals

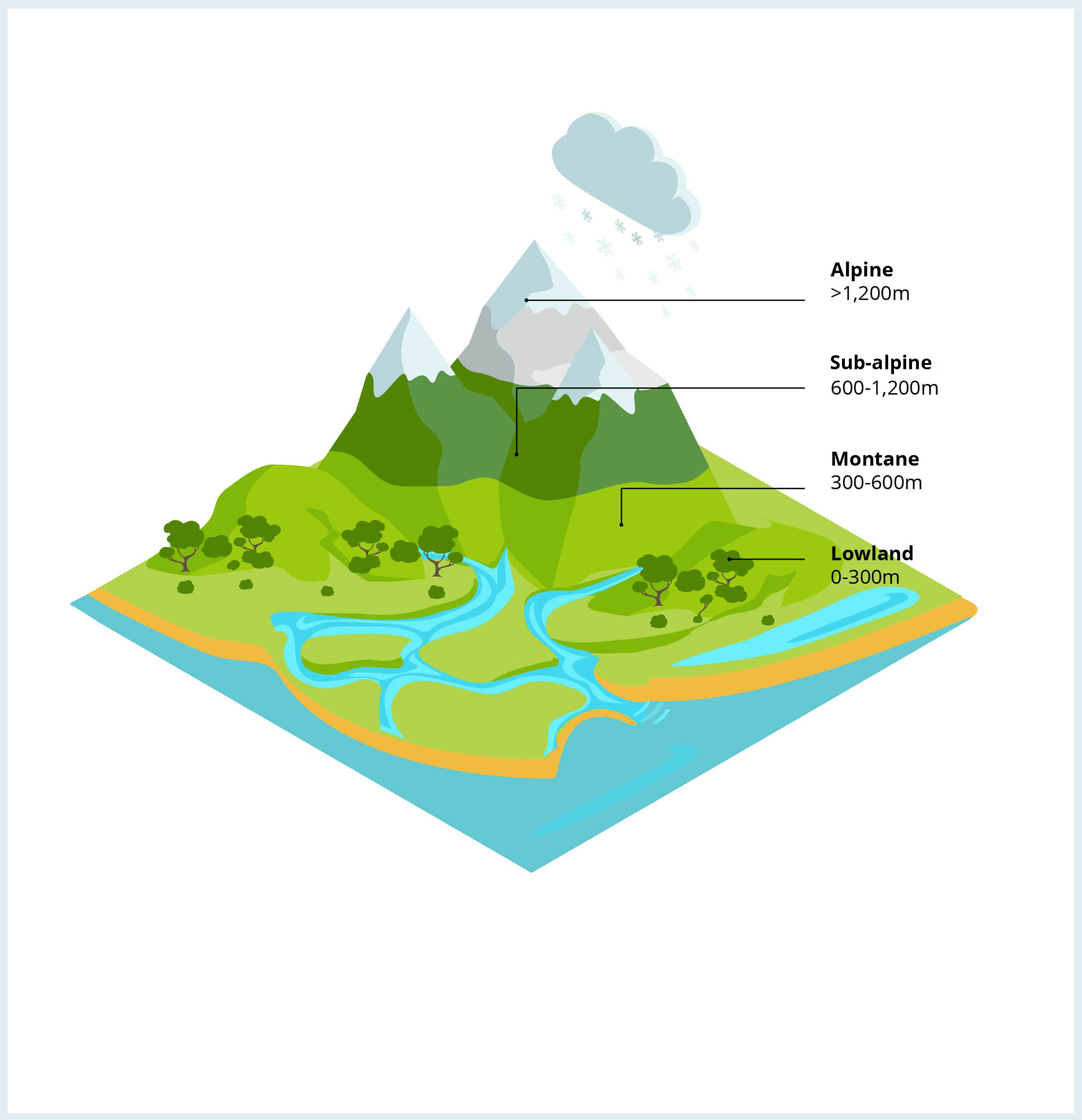

Elevation zones and changes in habitat quality

This cross-section of the landscape in Waitaha shows our four elevation zones: alpine, sub-alpine, montane and lowland.

The loss in hectares of high and medium-quality habitat to low-quality habitat for the four elevation zones between 1996 and 2018 is shown in the table below.

During this period, 55 hectares of high-quality alpine habitat degraded to become medium-quality habitat.

Sub-alpine, montane and lowland zones showed 57,300ha of high- to medium-quality habitat was degraded into low-quality habitat – approximately half the size of Banks Peninsula.

Each of the four elevation zones supports plants and animals that can make the zone their home.

The photos below the table show examples of these.

| Elevation | Terrain | Low value | Medium value | High value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| >1200m | Alpine | 0 | +55 ha | −55 ha |

| 600–1200m | Sub-alpine | +13677 ha | −5098 ha | −5098 ha |

| 300–600m | Montane | +29233 ha | −9359 ha | −9359 ha |

| 0–300m | Lowland | +14404 ha | −14014 ha | −390 ha |

| Ownership | Habitat quality | Change |

|---|---|---|

| Public | High | −6,175 Ha |

| Med | −3,012 Ha | |

| Low | +9,187 Ha | |

| Private | High | −10,340 Ha |

| Med | −38,476 Ha | |

| Low | +48,815 Ha |

Issue: Fragmentation of indigenous vegetation across the landscape of Waitaha

Habitat fragmentation

Land use change

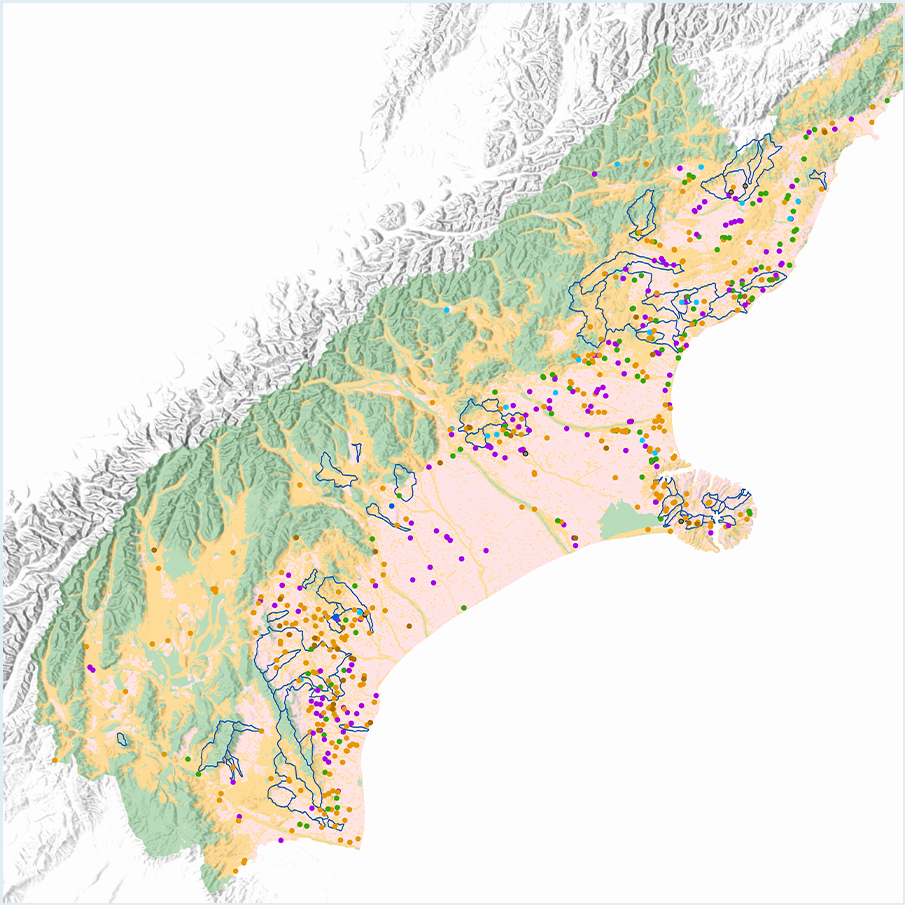

The indigenous biodiversity of Waitaha exists within largely fragmented habitats with limited connecting corridors. People’s use of land is, overall, the biggest cause of ongoing loss of indigenous biodiversity.

Fragmentation of natural areas through ongoing land use change has produced many isolated remnants that are important for biodiversity but vulnerable to continuing degradation through increased edge effects, being too small, and too isolated from other remnants to be sustainable.

We find less biodiversity within fragments. Fragments are also more vulnerable due to their size and shape where a greater proportion of a fragment is exposed to outside influence. This is called the edge effect.

Edge effects make fragments more susceptible to invasion by weeds and pest animals, to changes in environmental conditions such as wind, light and temperature, and to browsing, where farmed animals have access from a fence line for example.

Biodiversity fragments are only sustainable when they are close enough to other remnants and they can share ecosystem processes like seed dispersal, pollination and providing food and shelter for animals that travel between fragments.

Disconnection between indigenous ecosystems across the region is a significant obstacle in maintaining and protecting these fragmented remnants of indigenous biodiversity. Riccarton Bush in Christchurch/Ōtautahi is a prime example of a small, isolated remnant that now relies on interventions to remain viable.

Climate change is likely to exacerbate pressures on the remaining fragments and corridors, such as riparian habitat along braided rivers, compounding the stresses on already vulnerable habitats and the biodiversity within them. For example, the nesting habitat for native birds that rely on the remaining areas of bare shingle and gravel in braided riverbeds will be further constrained and at risk from more frequent flooding.

This map shows the distribution of indigenous vegetation across the Waitaha region in 2018.

Indigenous ecosystems across Waitaha

Changes between indigenous and exotic vegetation

The following tables show the most common transformations between indigenous and exotic vegetation over 20 years (between 1996 and 2018).

The first table shows that indigenous land cover continues to be lost, with remnant vegetation on glacial outwash and alluvial outwash surfaces (such as those found in the Mackenzie Basin/Te Manahuna) experiencing the greatest loss, primarily to high-producing grassland. For tussock grassland, the greatest loss is to exotic forest.

The second table shows that, under the right conditions, exotic land cover can revert to indigenous vegetation. Areas of gorse and broom are known to act as nurse cover assisting the regeneration of broadleaved indigenous vegetation, with Hinewai Reserve on Banks Peninsula/Horomaka standing out as a well-known example. In some places both low-producing and high-producing grassland can revert back to grey scrub and mānuka/kānuka, and to a lesser extent, broadleaved indigenous vegetation. Reversion to indigenous vegetation cover can only occur where there is existing indigenous cover close enough to provide a source of seeds.

| What started as… | Is now… | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| High producing grassland | Low producing grassland | Exotic forest | |

| Tussock grassland | 18 ha | 90 ha | 2,195 ha |

| Depleted grassland | 6,294 ha | 3,036 ha | 1,091 ha |

| Fernland | 90 ha | 82 ha | 426 ha |

| Mānuka and kānuka | 868 ha | 2,112 ha | 2,015 ha |

| Broadleaved indigenous | 143 ha | 198 ha | 623 ha |

| Grey scrub | 780 ha | 1,357 ha | 205 ha |

| What started as… | Is now… | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Grey scrub | Mānuka and kānuka | Broadleaved indigenous | |

| Gorse & Broom | 0 ha | 5 ha | 135 ha |

| Low producing grassland | 1,020 ha | 3,970 ha | 702 ha |

| Forest harvested | 4 ha | 50 ha | 28 ha |

| High producing grassland | 27 ha | 921 ha | 309 ha |

| Exotic forest | 4 ha | 41 ha | 10 ha |

Issue: Forestry impacts on terrestrial biodiversity in Waitaha

Wilding conifers

Forestry has a role to play in reducing greenhouse gas emissions in Waitaha. The Government is reviewing the way that carbon sequestration is estimated, including recognising carbon storage by indigenous forest management practices. This will assist with encouraging greater commitment to the planting of indigenous forests which will positively impact terrestrial biodiversity.

Although exotic forests may improve habitat for indigenous species, this is generally only seen where existing biodiversity values were already low or in a degraded state. More often, exotic forests tend to be established on farmland in the process of reverting to indigenous vegetation cover that provides valuable habitat for indigenous fauna.

The establishment of exotic forests in Waitaha hill country is often preceded by the clearance of existing vegetation. This might be undertaken through the use of controlled fires, the use of herbicides, mechanical means or a combination of these. Vegetation clearance carried out before afforestation is not controlled by the National Environmental Standards for Plantation Forestry (NES-PF) but in some areas protections are in place where these areas are identified as Significant Natural Areas by district plans.

Indigenous vegetation and habitats for indigenous fauna that persist following initial vegetation clearance and tree planting are often extinguished as the exotic trees grow.

Once exotic forests are established and the trees start to mature, the trees can provide a seed source for self-sown exotic trees (wilding trees). Wilding trees spread in Waitaha can impact many different values. For indigenous biodiversity, wilding trees out-compete and smother indigenous plant communities, can alter the environments that are favourable to indigenous fauna and flora, can dry out wetlands and riparian areas, and impact the hydrological functions of ecosystems.

Exotic conifer forests are flammable and have a high fuel load which poses a risk to biodiversity values on surrounding land in the event of a wildfire. Climate change projections for Waitaha indicate the risk of wildfire will increase.

Consented forestry activity

This map shows forestry activities consented by us since 2019. Resource consents are required for forestry activities that are not consistent with the values of important landscapes or areas of significant biodiversity. Resource consents are also required where there is a high risk of wilding tree spread.

While most consented forestry activity has occurred on land with low habitat quality, there has been a significant amount of land with higher habitat quality converted to exotic forestry which reduces the habitat quality and associated biodiversity values.