Marine biodiversity

The coastal environment in Canterbury/Waitaha is ecologically abundant and diverse, with a broad range of habitats. It includes reef systems, a submarine canyon, muddy and sandy harbours, rocky shore platforms and headland cliffs, river mouths, estuaries, lagoons, and dunes. These habitats support a rich diversity of plant and animal species, such as seabirds, marine mammals, fish, invertebrates and seaweeds - many of which are recognised as taonga species.

Here are the current issues faced by our marine ecosystems and biodiversity in Waitaha.

Issue: Protection of rare, threatened, keystone or culturally significant aquatic species and habitats

Unique species in our coastal marine area, include:

Unique species in our coastal marine area, include:

- Hector’s dolphins/tutumairekurai

- white-flippered, yellow-eyed penguins/hoiho and blue penguins/kororā

- Hutton’s shearwater/Kaikōura tītī

- Stokell’s smelt/pāraki

- katipō spiders

- several whale/tohorā species

- great white sharks/mangō tuatini and basking sharks/reremai.

Large populations of rare and endemic indigenous coastal plant species also call the region home, with a range of complex habitats found in river mouths, estuaries, coastal lagoons and hāpua.

Pressures on the coastal environment

Indigenous coastal habitats and species are threatened by a wide range of activities and cumulative pressures occurring both on land and in or near the coastal environment, such as land modification.

Climate change will put further pressures on these aquatic species and habitats, through:

- loss, erosion or degradation of habitat

- loss or reduction in foraging and breeding areas

- increased sea temperatures and ocean acidification, which could make it less suitable for indigenous species.

The protection of indigenous marine species and habitats is a high priority. Areas of Significant Natural Value and several marine protected areas have been established in our Regional Coastal Environment Plan (RCEP) to protect some of the rare, outstanding, and unique marine habitats and ecosystems in Waitaha as shown in the following map. Activities in these areas such as disturbance (including excavating, drilling and tunnelling), the erection or placement of structures and the removal of any natural material (including sand, shingle and shell) are highly restricted by the rules in the Plan.

Areas of Significant Natural Value show the existence of significant Māori cultural values, protected areas, wetlands, estuaries and coastal lagoons, marine mammals and birds, ecosystems, flora and fauna habitats, scenic sites, and historic places.

DOC Marine Reserves and mapped areas of important biodiversity in the Regional Coastal Environment Plan

Marine reserves in Waitaha including Hikurangi, Akaroa, and Pōhatu, have several fishery restrictions in place, mainly to protect the endangered Hector’s dolphin and whales. There are also Mātaitai reserves and Taiāpure mapped in the RCEP. These areas recognise and provide for traditional fishing and acknowledge local fisheries of special significance to iwi or hapū. There is no commercial fishing allowed in Mātaitai reserves.

Issue: Loss and degradation of estuarine and marine habitats

Habitat modification, fragmentation, degradation, and loss are widely considered some of the most serious threats to marine biodiversity. Habitat loss is particularly severe in coastal areas near urban environments. As the human population has increased in coastal areas, so has the pressure on coastal habitats through habitat change, increased pollution, and demand for coastal resources.

Importance of coastal habitats

Our important coastal habitats support high levels of biodiversity. They include wetlands, seagrass meadows, shellfish beds, kelp forests, and biogenic and rocky reefs. These habitats are important for nutrient cycling, food production and provision of habitat/refugia. They provide breeding grounds and nurseries, and natural barriers to erosion.

Changing coastal margins

Physical habitat loss through the draining of wetland areas; modification to the landward edge from reclamations, seawalls, and structures; dredging, overfishing, stock grazing, vehicle use and high recreational use, can reduce the biodiversity of habitats and aquatic species. Degraded water quality can also result in sedimentation and eutrophication, which further degrades habitats.

Climate change will result in increasing median sea levels which leads to large tides and greater inundation of coastal environments during storm events.

Coastal margins, and the ecosystems that they support, will migrate inland as sea level rises. The landward migration of coastal ecosystems is going to be constrained by human-made constraints, like rail and roading infrastructure. In many cases, these prevent the inland migration of coastal dunes/marginal environments, causing these ecosystems to be compressed and therefore degraded. Eventually, this may lead to the complete loss of the coastal margin environment in these areas, and the associated loss of these ecosystems. Some natural geographic features (such as sand dunes) and coastal protection works will limit the effects of sea level rise and coastal erosion in some localities.

Identifying and monitoring critical habitats is important to ensure that appropriate controls on activities can be identified and implemented in the coastal marine area to ensure they do not have adverse effects. The RCEP manages the effects of indigenous biodiversity in the coastal marine area. The resource consent process assesses the effects and mitigation of specific activities on indigenous biodiversity.

Issue: Non-indigenous species threatening habitats and indigenous species

Non-indigenous (introduced or exotic) species (NIS) are recognised as one of the most significant threats to marine ecosystems in New Zealand/Aotearoa and Waitaha. Some NIS can become invasive and have significant adverse effects on marine ecosystems through predation, competition, and displacement of indigenous species, modifying natural habitats, altering ecosystem processes, and reducing overall biodiversity. NIS can also introduce and spread disease and parasites that cause fish, crustaceans, and shellfish stocks to collapse.

How marine pests establish

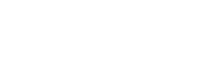

The main pathways for NIS introduction within the Waitaha region are biofouling of vessels (when aquatic organisms attach themselves to vessels), ballast tank water from vessels, operation of ports, aquaculture, and the introduction of structures within the coastal marine area. Other pathways include discharges of organic material from dredging (which occurs in Lyttelton/Whakaraupō Harbour) and the maintenance of moorings, marinas, jetties, and wharves. Photos of these artificial structures that impact coastal habitats are shown in the accompanying illustrations.

Increased sea temperatures through climate change will change species distribution by making it more suitable for new invasive species and less suitable for indigenous species.

Given the dynamic nature of the coastal marine area, the identification and management of NIS and diseases is far more complex and challenging than their terrestrial counterparts. Once established, they can be difficult to control and eradicate and they can spread quickly.

Marine pests already established in Waitaha

The number of established NIS in New Zealand/Aotearoa coastal waters is approximately 330. Approximately 18 have been recorded in the Port of Lyttelton/Whakaraupō. Several of these have been classified as pest species by the Ministry for Primary Industries/Manatū Ahu Matua, including:

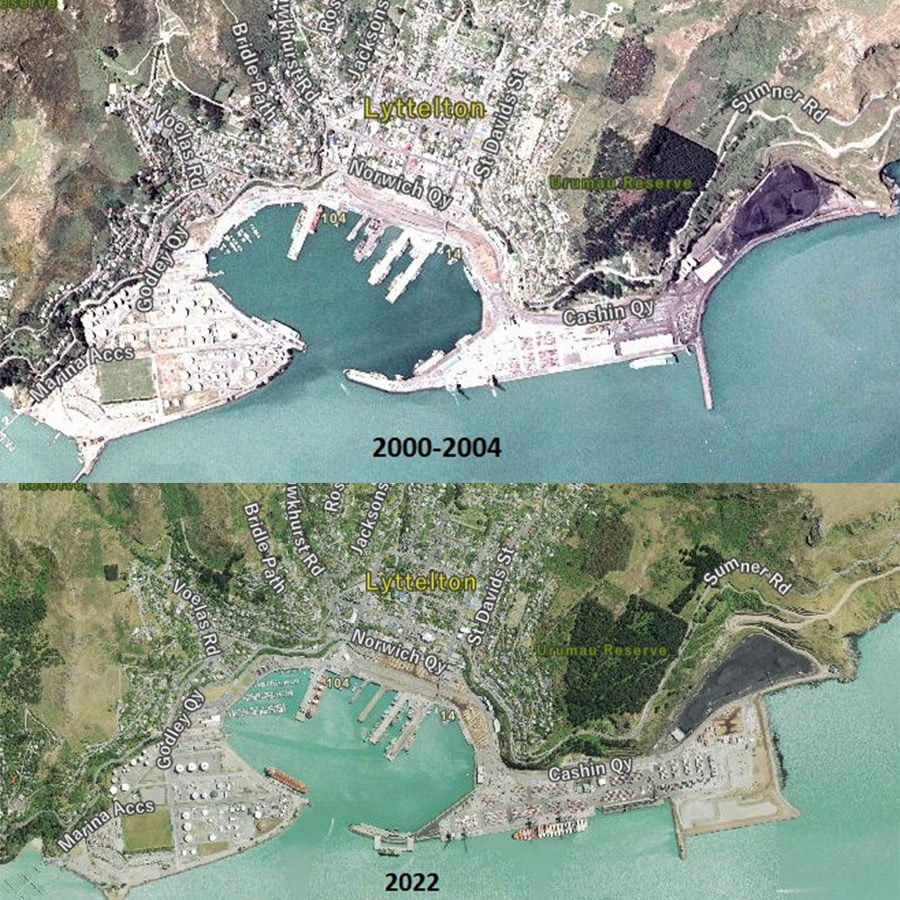

- Mediterranean fanworm (Sabella spallanzanii) – an invasive pest species that affects indigenous species by competing for food and space, preying on larvae, and disrupting natural ecological balance. (Pictured below, along with its distribution.)

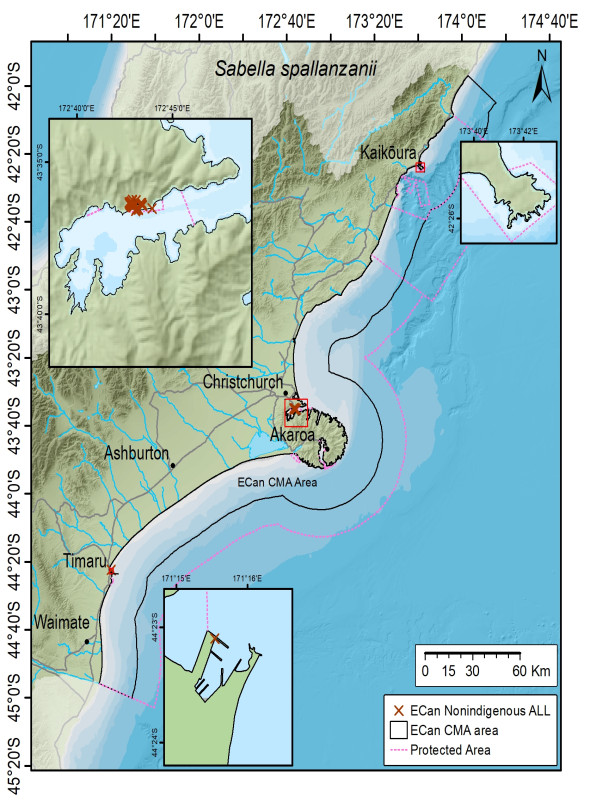

- Undaria/Asian kelp/wakame (Undaria pinnatifida) – an invasive pest species of kelp that has been known to compete with indigenous species, change the structure of ecosystems, and affect biodiversity. (Pictured below, along with its distribution.)

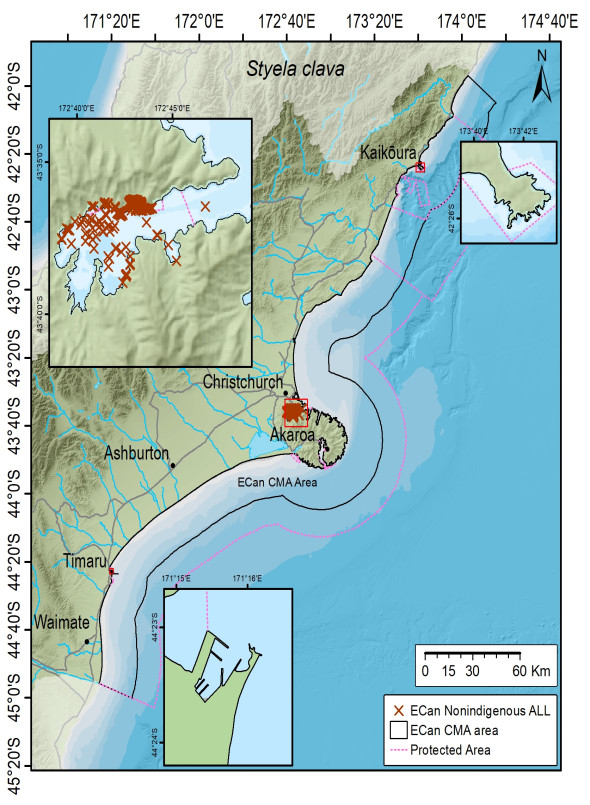

- Sea squirt/clubbed tunicate (Styela clava) – an invasive pest species that forms dense colonies and competes for space with other organisms, preys on larvae, and displaces indigenous and fisheries species. It poses a threat to biodiversity and the aquaculture industry. (Pictured below, along with its distribution.)

- Theora lubrica (bivalve mollusc) – a NIS found in the intertidal areas of Lyttelton/Whakaraupō Harbour and Akaroa Harbour.

- Barantolla lepte (worm) – a NIS found in the intertidal areas of Akaroa Harbour and Okain’s Bay.

- Hirayamaia mortoni (sand hopper) – a NIS found in the intertidal areas of Akaroa Harbour.

Distribution of Mediterranean fanworm, Undaria and sea squirt

Source: 2020 NIWA report

For more, visit our marine pests page.